When I was a biology major at West Liberty State College, plant taxonomy was offered in the spring semester. To me, thoughts of “spring” included sunshine, longer days, and warmer temperatures. But our “spring” semester actually began two weeks after the first day of winter, so frigid temperatures and snow, not wildflowers, greeted us that first day of our “spring” semester class.

During class, we sat through lectures and slides discussing how to approach the identification of plants. Basically, scientists group and identify flowering plants according to their reproductive structures: flowers, fruits and seeds. In some plants such as mosses, liverworts, horsetails, and ferns, the reproductive structures are: capsules, sporangia, sporophylls, indusium, sori, and spores — strange words to us students. In fact, the greatest difficulty we faced was learning, remembering, and understanding this new vocabulary. Each facet of nature study, whether it is fungi, beetles, or birds, etc., has its own unique vocabulary associated with it.

Mr. Berry, our plant taxonomy professor, announced that all labs (2 two-hour labs each week) would be conducted outdoors, weather permitting. My logic told me that meant our labs would meet inside until late March or possibly early April (“real” spring); however, that week, our very first lab was held outside. Our teeth chattered and our extremities numbed as the wind penetrated our meager clothing. Mr. Berry, with his great wool balaclava hat pulled over his ears, heavy coat and gloves, wool pants, thermal socks and insulated boots, stayed as warm as toast. He actually viewed our field trip as fun, even hinting that he was too warm. Needless to say, there was a method to his madness. After one of the most uncomfortable days of our lives, each of us came to future labs prepared for any and all weather conditions.

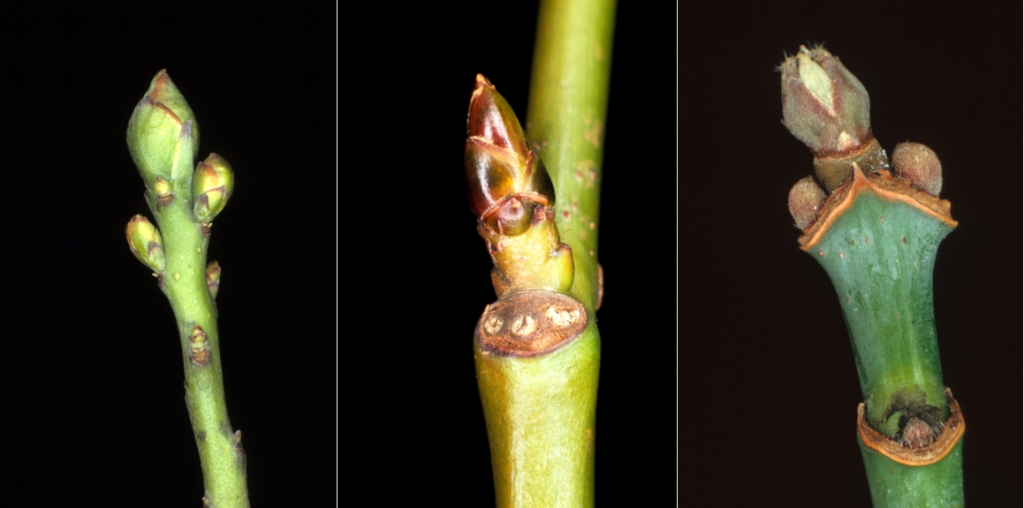

Winter deciduous tree identification became our first obstacle. The very idea of trying to distinguish one tree from another, without the benefit of comparing leaves, was foreign to us. Our class was informed that trees are easier and, in many ways, more reliably identified in the winter months. By looking for certain distinguishing characteristics found only on the twigs, most trees are relatively easy to identify. A few of the most significant new vocabulary words were: (1) terminal bud — the bud at the end of each twig remaining after the leaves fall, (2) leaf scar — a patch, differing in color and texture from the rest of the twig, where a leaf was attached, (3) leaf bud — a round or pointed growth, centered (occasionally off-center) just above or almost inside a leaf scar, and (4) vascular bundle scars — small dots or lines on the surface of the leaf scar.

scars (Photo (c) Bill Beatty)

Anyone who wants to identify winter trees needs a hand lens (at least 10x) to view these tiny structures. To become more familiar with these characteristics, find a tree with large buds and leaf scars such as Horse-chestnut, Buckeye, Tree-of-heaven, Butternut, or Kentucky Coffeetree. Practice using the hand lens to find those 4 parts of a winter tree twig.

“MAD-Cat-Horse“ This is an important acronym for: Maple, Ash, Dogwood, Catalpa, and Horse-chestnut (includes Buckeyes). This represents all the deciduous trees in West Virginia, and many other states, which have opposite branching. If the branches, leaf buds, and scars are not opposite each other on the twig, then the tree is not a species in the MAD-Cat-Horse group. Oaks, cherry, elm, hickory, and other tree species have alternate branches, leaf buds, and leaf scars. The distinction between opposite branches and alternate branches is the first important step in winter tree ID.

Maples, especially Norway Maples, have always been my favorite winter twigs. This is probably because the leaf bud and scar resemble two eyes, a nose and, often, a smiling mouth. All maple leaf scars are crescent or V-shaped with three vascular bundle scars, one at each end (the eyes) and one lower in the middle (the mouth). The leaf bud (the nose) is just above the mouth, between the eyes.

Although leaf scars on all maples are similar, their terminal buds (where branches grow longer) and leaf buds are very different in the different species. For example, Sugar Maple buds are brown and pointed with small overlapping scales, while Norway Maple buds are also pointed, but fatter and burgundy-colored with larger overlapping scales. Red Maple and Silver Maple buds and scars are practically identical. But crush and smell the leaf or terminal buds of the Silver Maple, and your nose will be greeted by a rank odor. Red Maple terminal buds have no odor. Box Elder (Ash-leaved Maple) twigs are green. There is always a way to discern trees by their twigs.

The scaly, overlapping character of the maple buds is referred to as imbricate. Oaks, cherries, elms. sweet gum, and some other tree buds also have this imbricate or scaly, overlapping attribute, but they are in alternate locations. The opposite of imbricate is valvate. Valvate terminal bud scales meet along a distinct, usually longitudinal, line without overlapping. Yellow Poplar (Tuliptree) and Flowering Dogwood terminal buds are valvate.

Before we go on, a word of caution about Flowering Dogwood terminal buds. The large, round, whitish buds at the end of many dogwood twigs are actually next year’s flower buds. These flower buds are so obvious and unique on all except the youngest trees, there is no need to look for the tiny terminal buds. Once you view these distinctive flower buds, you will not forget them, and the winter identification of dogwoods will be indelible in your mind. I can easily visualize the springtime beauty of each Flowering Dogwood by the number of flower buds present. Some trees have hundreds.

Simple rules that are unique to certain trees or groups of trees provide shortcuts to winter identification. Only oaks usually have several terminal buds at the end of each twig. Similar to the characteristics of their leaves, red oak group terminal buds are pointed while white oak group buds are more rounded.

Black Walnut leaf scars are described as having a monkey-face or barn owl-face.

American Elm twigs are very fuzzy, while those of the Slippery Elm are slightly fuzzy or smooth.

Sassafras, Sweetgum, and Box Elder (Ash-leaved Maple) twigs are green (called “photo stems”). Sassafras is spicy to smell or taste; Sweetgum leaf buds and scars are alternate; and Box Elder, being a maple, has leaf buds and scars that are opposite.

American Beech terminal buds are long, slender and sharply pointed, providing a slightly painful jab if pushed against.

The terminal bud of the White Ash reminds me of a king’s crown as he sits upon his throne.

I remember traits of numerous creatures due to their association with some other memorable thought. As you study and learn the identification of more winter tree twigs, you, too, will find some twigs more notable due to associations you will make.

An excellent guide to winter twig identification is , Fruit Key & Twig Key to Trees and Shrubs, by William M. Harlow. This book uses a dichotomous key approach with black and white photo illustrations. It covers virtually all trees, as well as shrubs and many woody vines, found in West Virginia. The fruit key also includes evergreens.

Wintertime is not the time to remain indoors, especially with a multitude of twigs begging to be examined. If the weather is too cold, wait for a warmer winter day, or simply cut the twigs you want to identify and bring them indoors. Early morning is the best time to go outside, for if you do so, in addition to making the acquaintance of many trees, you will reap the additional benefits of solitude, opportunities to observe wildlife, and the musical peeps, chips, and calls of our winter birds.