Bill’s Books

Creature Feature https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2023/04/21/creature-feature/

Project Boys https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2020/03/17/project-boys/

Wild Plant Cookbook https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2016/09/30/wild-plant-cookbook/

Rainbows, Bluebirds and Buffleheads https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2016/08/06/rainbows-bluebirds-and-buffleheads/

Birds

A Holy Grail in Bird Photography https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2024/02/27/a-holy-grail-in-bird-photography/

Providing Water for Birds in the Winter https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2023/11/01/providing-water-for-birds-in-the-winter/

West Virginia Mountain State Bird Festival, 2023, and More – Some Highlights. https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2023/06/14/west-virginia-mountain-state-bird-festival-2023-and-more-some-highlights/

The 2023 Ralph K. Bell Memorial Walk https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2023/05/29/the-2023-ralph-k-bell-memorial-walk/

Indigo Bunting and Ovenbird — Two Bird Photos… by request. https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2023/05/26/indigo-bunting-and-ovenbird-two-bird-photos-by-request/

West Virginia Bird Discovery Weekend at Blackwater Falls State Park, June 2-4, 2023 https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2023/05/03/west-virginia-bird-discovery-weekend-at-blackwater-falls-state-park-june-2-4-2023/

Attracting and Photographing Pileated Woodpeckers https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2022/02/21/attracting-and-photographing-pileated-woodpeckers/

A Rufous Hummingbird in Brooke County, West Virginia and a Design for a Cold Weather Nectar Feeder https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2021/11/14/a-rufous-hummingbird-in-brooke-county-west-virginia-and-a-design-for-a-cold-weather-nectar-feeder/

Birds-Camping-Hiking and more on Dolly Sods – 2021 https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2021/10/19/birds-camping-hiking-and-more-on-dolly-sods-2021/

How Do Birds Know? https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2021/02/18/how-do-birds-know/

Pine Siskin Irruption – 2020 https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2021/01/01/pine-siskin-irruption-2020/

Saga of the Green Herons https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2020/08/17/saga-of-the-green-herons/

Oriole Fallout — in Rhyme (by Jan Runyan) https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2020/05/19/oriole-fallout-in-rhyme-by-jan-runyan/

Bill’s Bark Butter Recipe https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2020/02/19/bills-bark-butter-recipe/

Dolly Sods Adventures – 2019 https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2019/11/22/dolly-sods-adventures-2019/

The Allegheny Front Migration Observatory (AFMO), Hiking, Wildflowers and More on Dolly Sods – late September, 2018 https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2019/03/04/the-allegheny-front-migration-observatory-afmo-hiking-wildflowers-and-more-on-dolly-sods-late-september-2018/

Rainbows, Bluebirds and Buffleheads https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2016/08/06/rainbows-bluebirds-and-buffleheads/

Bluebirds and Blue Birds are not Blue! https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2016/05/22/bluebirds-and-blue-birds-are-not-blue/

Hail, Hail the Gang’s All Here….Pine Siskins………by Jan Runyan https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2016/01/07/hail-hail-the-gangs-all-here-pine-siskinsby-jan-runyan/

A Bluebird Brings Happiness…..by Jan https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2015/11/24/a-bluebird-brings-happiness-by-jan/

Not GOLDFINCHY . . . . . . by Jan Runyan https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2015/07/08/not-goldfinchy-by-jan-runyan/

Banding a Dinosaur https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2015/05/26/banding-a-dinosaur/

Welcome Home My Little Chickadee — by Jan https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2015/04/27/welcome-home-my-little-chickadee-by-jan-runyan/

American Goldfinch Heaven https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2015/04/26/american-goldfinch-heaven/

Return of the “Gold”finches….almost — by Jan https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2015/03/23/return-of-the-goldfinches-almost-by-jan/

Behold…the American Goldfinches are coming. https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2015/03/16/behold-the-american-goldfinches-are-coming-2/

Owls

Owls In the Family… part two… Eastern Screech-owls https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2018/02/13/owls-in-the-family-part-two-eastern-screech-owls/

Owls In the Family…Great Horned Owls https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2017/02/05/owls-in-the-family-great-horned-owls/

Wildflowers, Trees, and Botany

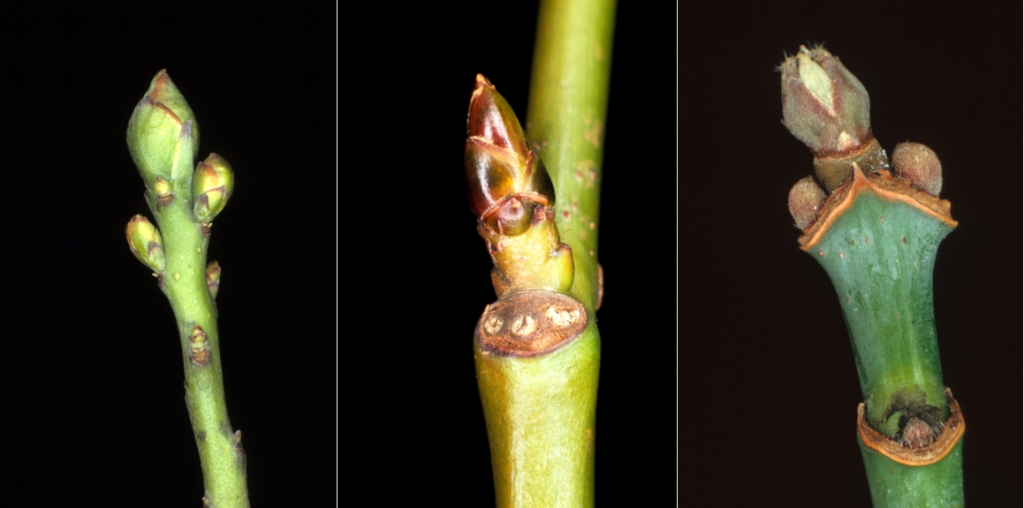

Winter Offers the Best Opportunity for Tree Identification https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2024/01/31/winter-offers-the-best-opportunity-for-tree-identification/

A Walk on a Beautiful Early Spring Day https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2023/03/30/a-walk-on-a-beautiful-early-spring-day/

A Secret Place https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2022/10/13/a-secret-place/

“Pickin’ up pawpaws, put ‘em in my pocket….” by Jan Runyan https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2019/10/22/pickin-up-pawpaws-put-em-in-my-pocket-by-jan-runyan/

Plant Friends Without Their Flowers https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2019/04/07/plant-friends-without-their-flowers/

Friendly Faces https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2018/04/09/friendly-faces/

Kayaking the Headwaters of the Blackwater River…and Searching for Wildflowers https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2017/08/25/kayaking-the-headwaters-of-the-blackwater-river-and-searching-for-wildflowers/

Shirley Temple Wildflowers…..by Jan Runyan https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2016/03/09/shirley-temple-wildflowers-by-jan-runyan/

Summer Wildflowers of the Dolly Sods Wilderness https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2015/07/22/summer-wildflowers-of-the-dolly-sods-wilderness/

Edible and Medicinal Plants

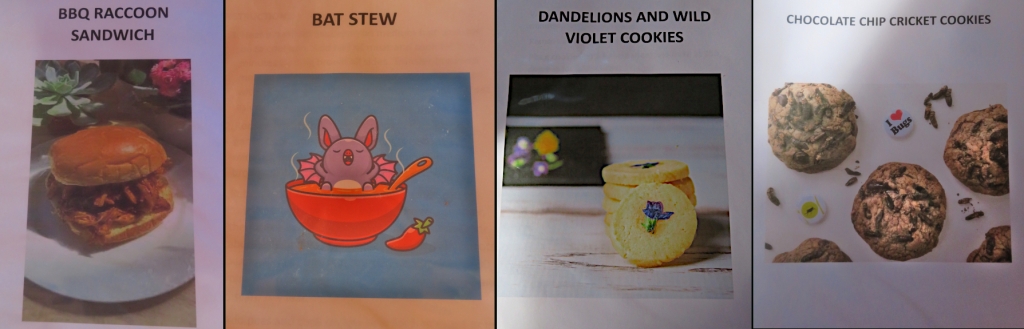

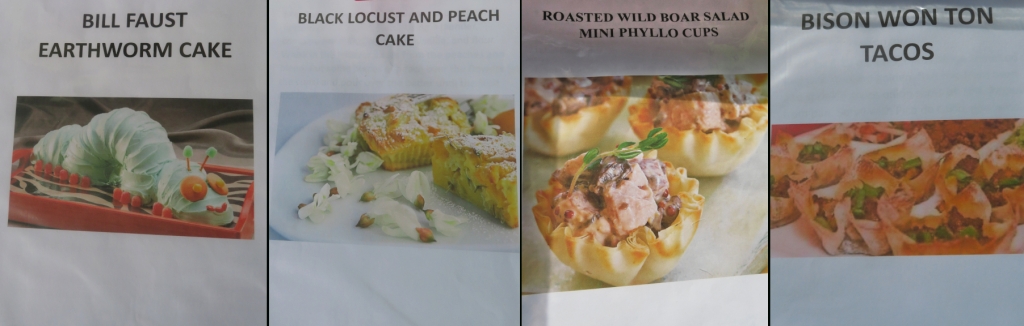

The 54th annual Nature Wonder Weekend at West Virginia’s North Bend State Park — What we did. https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2023/09/23/the-54th-annual-nature-wonder-weekend-at-west-virginias-north-bend-state-park-what-we-did/

Goldenseal a.k.a. Yellowroot https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2020/04/19/goldenseal-a-k-a-yellowroot/

Common Chickweed — My Favorite Spring Wild Edible Green https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2020/04/10/common-chickweed-my-favorite-spring-wild-edible-green/

“Pickin’ up pawpaws, put ‘em in my pocket….” by Jan Runyan https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2019/10/22/pickin-up-pawpaws-put-em-in-my-pocket-by-jan-runyan/

Wild Plant Cookbook https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2016/09/30/wild-plant-cookbook/

Nature Photography

A Holy Grail in Bird Photography https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2024/02/27/a-holy-grail-in-bird-photography/

Attracting and Photographing Pileated Woodpeckers https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2022/02/21/attracting-and-photographing-pileated-woodpeckers/

The Story Behind Bill’s photo credits https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2022/01/11/the-story-behind-bills-photo-credits/

Make Your Photos Pop! https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2015/10/26/make-your-photos-pop/

Bill’s Arboretum

A Tale of Two Winterberries https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2022/10/26/a-tale-of-two-winterberries/

Adding Pawpaw Trees to Our Arboretum https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2020/07/15/adding-pawpaw-trees-to-our-arboretum/

Our Garden and Property

Bill’s Spruce Adventure — by Jan Runyan https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2020/07/24/bills-spruce-adventure-by-jan-runyan/

Bill and Jan’s Observations

Lightning Bugs/Fireflies — https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2023/07/20/lightning-bugs-fireflies/

A Serendipity Day — Beyond Maitake Mushrooms and Pawpaws https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2022/10/02/a-serendipity-day-beyond-maitake-mushrooms-and-pawpaws/

Springtime https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2021/03/04/springtime/

The first day of spring …. Is a personal thing. https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2021/01/25/the-first-day-of-spring-is-a-personal-thing/

An Unexpected Nature Surprise https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2020/09/06/an-unexpected-nature-surprise/

Don Pattison – A Soft-spoken Gentle Friend https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2020/06/09/don-pattison-a-soft-spoken-gentle-friend/

The First Day of Spring – For Me https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2020/03/12/the-first-day-of-spring-for-me/

Finally — A Winter Hike https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2020/02/08/finally-a-winter-hike/

Tick—ed Off: a tick—lish situation https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2016/01/19/tick-ed-off-a-tick-lish-situation/

Ladybug Hibernation…a fortunate discovery https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2015/04/19/ladybug-hibernation-a-fortunate-discovery/

Contemplating Mortality https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2015/04/08/contemplating-mortality/

That Bird Vanished!…a shrew-d sighting — by Jan https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2015/03/28/that-bird-vanished-a-shrew-d-sighting-by-jan/

Another sign that spring is just around the corner. https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2015/03/10/another-sign-that-spring-is-just-around-the-corner/

Spring Is Here…by Jan https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2015/03/08/spring-is-here-by-jan/

Bill and Jan’s Celebrations and Adventures

Hiking Adventures in the West Virginia Highlands – In Celebration of Cindy https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2020/01/26/hiking-adventures-in-the-west-virginia-highlands-in-celebration-of-cindy/

From West Virginia to Nags Head, North Carolina — the Outer Banks https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2020/01/24/from-west-virginia-to-nags-head-north-carolina-the-outer-banks/

Big Run Bog – An Unexpected Road Trip – Saturday, August 10, 2019 https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2019/08/12/big-run-bog-an-unexpected-road-trip-saturday-august-10-2019/

West Virginia University’s Hemlock Trail near Cooper’s Rock State Forest – May 8, 2019 https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2019/05/26/west-virginia-universitys-hemlock-trail-near-coopers-rock-state-forest-may-8-2019/

A Celebration with Friends in the Mountains of West Virginia – Great Food, Laughing, Hiking, Singing and Spending Time with Each Other at Some of our Favorite Natural Places https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2018/10/23/a-celebration-with-friends-in-the-mountains-of-west-virginia-great-food-laughing-hiking-singing-and-spending-time-with-each-other-at-some-of-our-favorite-natural-places/

Snaggy Mountain Area, Garrett State Forest, MD – Late June 2018 https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2018/07/06/snaggy-mountain-area-garrett-state-forest-md-late-june-2018/

Kayaking the Headwaters of the Blackwater River…and Searching for Wildflowers https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2017/08/25/kayaking-the-headwaters-of-the-blackwater-river-and-searching-for-wildflowers/

Dolly Sods

Birds-Camping-Hiking and more on Dolly Sods – 2021 https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2021/10/19/birds-camping-hiking-and-more-on-dolly-sods-2021/

Just Us – Hiking on Dolly Sods https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2020/10/14/just-us-hiking-on-dolly-sods/

A Different Dolly Sods Adventure — 2020-style https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2020/10/03/a-different-dolly-sods-adventure-2020-style/

Listening to Creation https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2019/12/02/listening-to-creation/

Dolly Sods Adventures – 2019 https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2019/11/22/dolly-sods-adventures-2019/

The Allegheny Front Migration Observatory (AFMO), Hiking, Wildflowers and More on Dolly Sods – late September, 2018 https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2019/03/04/the-allegheny-front-migration-observatory-afmo-hiking-wildflowers-and-more-on-dolly-sods-late-september-2018/

A Grandkid Discovers the Nature of Dolly Sods https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2017/07/31/a-grandkid-discovers-the-nature-of-dolly-sods/

Summer Wildflowers of the Dolly Sods Wilderness https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2015/07/22/summer-wildflowers-of-the-dolly-sods-wilderness/

Canaan Valley

Canaan Valley for Fall Color and More – October 2020 https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2020/10/18/canaan-valley-for-fall-color-and-more-october-2020/

Canaan Valley State Park and Canaan Loop Road – Late June, 2018 https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2018/07/20/canaan-valley-state-park-and-canaan-loop-road-late-june-2018/

Idleman’s Run Trail in the Canaan Valley National Wildlife Refuge – Late June https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2018/07/16/idlemans-run-trail-in-the-canaan-valley-national-wildlife-refuge-late-june/

Beall Tract – Canaan Valley National Wildlife Refuge – Late June, 2018 https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2018/07/12/beall-tract-canaan-valley-national-wildlife-refuge-late-june-2018/

Kayaking the Headwaters of the Blackwater River…and Searching for Wildflowers https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2017/08/25/kayaking-the-headwaters-of-the-blackwater-river-and-searching-for-wildflowers/

Magee Marsh

Howard Marsh 2023 https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2023/08/23/howard-marsh-2023/

Magee Marsh 2023 https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2023/07/27/magee-marsh-2023-for-birds-and-much-more/

Beyond Magee Marsh — 2022 — Maumee Bay, Camp Sabroske, Howard Marsh, Metzger Marsh https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2022/09/10/beyond-magee-marsh-2022-maumee-bay-camp-sabroske-howard-marsh-metzger-marsh/

Beyond Magee Marsh – 2022 – Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2022/09/03/beyond-magee-marsh-2022-ottawa-national-wildlife-refuge/

Magee Marsh Birding 2022 https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2022/08/23/magee-marsh-birding-2022/

Brooks Bird Club

The Brooks Bird Club’s 90th Anniversary at Hawk’s Nest State Park https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2022/11/26/the-brooks-bird-clubs-90th-anniversary-at-hawks-nest-state-park/

The Brooks Bird Club’s Fall Reunion/Meeting 2021 — Cedar Lakes Conference Center https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2021/11/09/the-brooks-bird-clubs-fall-reunion-meeting-2021-cedar-lakes-conference-center/

Master Naturalist

Teaching Master Naturalists in Scenic Canaan Valley, WV – 2022 https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2022/09/25/teaching-master-naturalists-in-scenic-canaan-valley-wv-2022/

Master Naturalist Conference 2021 at Canaan Valley State Park https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2021/08/27/master-naturalist-conference-2021-at-canaan-valley-state-park/

The Field Trip that….SUCKED! https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2015/06/17/the-field-trip-that-sucked/

Mountain State Bird Discovery Weekend

West Virginia Mountain State Bird Festival, 2023, and More – Some Highlights. https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2023/06/14/west-virginia-mountain-state-bird-festival-2023-and-more-some-highlights/

West Virginia Bird Discovery Weekend at Blackwater Falls State Park, June 2-4, 2023 https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2023/05/03/west-virginia-bird-discovery-weekend-at-blackwater-falls-state-park-june-2-4-2023/

Mountain State Bird Discovery Weekend 2022 at Blackwater Falls State Park https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2022/07/10/mountain-state-bird-discovery-weekend-2022-at-blackwater-falls-state-park/

What a Great Nature Workshop Weekend! (due to Covid we had to hold this weekend 2 1/2 weeks later than usual and change the emphasis to “Plants and Other Nature”) https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2020/08/07/what-a-great-nature-workshop-weekend/

Bird Discovery Weekend at Blackwater Falls State Park – 2019 – what we did. https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2019/06/11/bird-discovery-weekend-at-blackwater-falls-state-park-2019-what-we-did/

Oglebay Institute’s Adult Nature Studies Camp at Terra Alta, WV (Mountain Nature Camp)

Mountain Nature Camp for Adults – June 16-22, 2024 https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2024/04/07/mountain-nature-camp-for-adults-june-16-22-2024/

Oglebay Institute’s Mountain Nature Camp for adults – 2022 – What We Did https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2022/07/31/oglebay-institutes-mountain-nature-camp-for-adults-2022-what-we-did/

Oglebay Institute’s Mountain Nature Camp (for adults)-2021 – So good to be back at “Good Ol’ TA”. https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2021/07/07/oglebay-institutes-mountain-nature-camp-for-adults-2021-so-good-to-be-back-at-good-ol-ta/

Mountain Nature Camp for Adults – June 2018 – What We Did. https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2018/08/21/mountain-nature-camp-for-adults-june-2018-what-we-did/

West Virginia Wildflower Pilgrimage

West Virginia Wildflower Pilgrimage – May 9-12, 2024 https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2024/03/27/west-virginia-wildflower-pilgrimage-may-9-12-2024/

2022 Our West Virginia Wildflower Pilgrimage Trip https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2022/05/27/2022-our-west-virginia-wildflower-pilgrimage-trip/

2019 West Virginia Wildflower Pilgrimage – Our Trip https://wvbirder.wordpress.com/2019/05/29/2019-west-virginia-wildflower-pilgrimage-our-trip/